By appointment only

Set opening hours

All You Need to Know About the McLaren Vale Wine Region

Explore the McLaren Vale wine region from its early beginnings to the players that define it today. Learn about the grape varieties, climate, soils and wine styles that make it tick.

History

McLaren Vale can lay claim to being South Australia’s first wine-growing region, pipping the Barossa Valley by a few years

Read moreGeography, Soils & Climate

McLaren Vale has many subregions that producers reference, such as Blewitt Springs, McLaren Flat, Seaview, Sellicks and Willunga, but these are not enshrined in law, with as many as 19 posited by the McLaren Vale Grape Wine & Tourism Association, who produced a detailed geological map of the region in 2010.

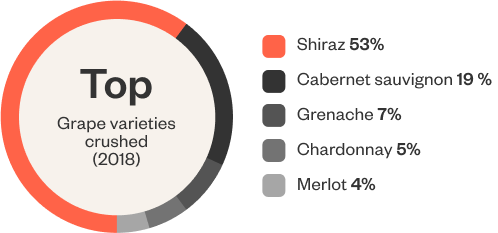

Read moreGrape Varieties & Wine Styles

Ask a McLaren Vale winemaker to nominate the region’s most emblematic variety and you’ll often hear the word grenache. Which is odd really.

Read moreTop Wine Producers and Cellar Doors

Our list of the best cellar doors to visit, and the wine producers you need to know, from established icons to those cutting new paths.

The Iconic Wineries

These are benchmark wineries that have helped to shape the region, and they stand as reference points today.

View listThe New Wave Wineries

The makers that are paving a new way, taking inspiration from the past and shaping a new future.

View listCellar Doors

There’s no better way to engage with makers than to visit them onsite, and these are some of the best wine experiences in the region.

View listWhen You’re There

Travelling to a wine region isn’t always just about the wine. Discover our lists of the best places to eat – both casual and refined – our top accommodation recommendations – from budget to luxury – and our go-to lists of local attractions – from shopping to outdoor adventures.

Shopping & Other Attractions in McLaren Vale

From shopping for regional specialties to organising an outdoor adventure, these are some of the region’s top attractions.

View listAccommodation in McLaren Vale

Whether splashing out or sticking to a budget, these are some of the best places to stay in McLaren Vale.

View listEating Out – McLaren Vale's Best Restaurants and Cafés

Whether it’s a lunch at the pub or dinner in a celebrated restaurant, no visit to McLaren Vale is complete without exploring the dynamic food scene.

View list