While the Barossa and Eden Valleys are both distinct regions with individual characteristics, they are also inseparable in many ways, sharing some similarities and correlations, and with key wine producers often spilling into both. So, while the regional differences are essential to note, it is helpful to consider them together, especially when visiting.

History

The Barossa has a distinctly German accent, with vestiges of the early migration of Prussian Lutherans palpable to this day. While the South Australian colony was naturally settled by the British, a shared religious piety saw often disenfranchised and increasingly persecuted Silesian (Silesia is a province of what was then Prussia but now is contained by Poland’s borders) farmers drawn to the colony to escape the unification of the Protestant church by King Friedrich Wilhelm III.

George Fife Angas is largely seen as the architect of the South Australian colony. Having made his fortune in New South Wales, he shifted his focus to the south-west, heading up the South Australian Company. He was a deeply religious man, and that the territory was settled by people of strong moral fibre was essential. Those Prussian farming families were just that in his eyes, and the skills and longstanding self-sufficiency made them ideal candidates to shape the new settlement. Ships were first dispatched in 1841, with nearly 500 families eventually eagerly taking up the offer – though it took some wrangling to approve the papers.

The Barossa is generally good farming land, and the mixed agriculture of these settlers inevitably included all manner of fruiting plants, and with a subsequently proven suitability to viticulture, wine grapes thrived. The warm climate also encouraged good ripeness in most years, which was an essential component for producing fortified wine that would become the country’s most popular styles towards the end of the 19th century and up until the latter half of the 20th century.

The Barossa was officially named by Colonel William Light in 1837 (Light had fought at the Battle of Barrosa in 1811 – it was misspelled here when officially registered), though it was not surveyed until 1839. Between 1842 and ‘43, the towns of Bethany, Angaston, Krondorf, Penrice, Light Pass and Ebenezer were founded, and grapes were planted. Unsurprisingly, the Prussian settlers planted riesling – though it was subsequently often distilled, being generally too delicate for the warmer areas without the aid of modern technology – along with shiraz, cabernet sauvignon, mourvèdre (locally called mataro) and semillon also notably being planted.

It is no secret that a precious resource of those early plantings still exist today, with the 1843 shiraz vines owned by Langmeil thought to be the oldest. In the Eden Valley, while the ancient vines are no longer there, the grape material lineage of the riesling planted by Joseph Gilbert in 1847 persists at Pewsey Vale in the Eden Valley. Those vines were the first in the region, and the replanted ones are now officially old vines (there’s an official Barossa charter: Centenarian 100+ years, Survivor Vine 70+ years and Old Vine 35+ years), with the vineyard re-established by Wyndham Hill-Smith in 1961. Hill of Grace’s 1860s shiraz vines also stand out as some of the region’s oldest.

In the Barossa Valley, the oldest mourvèdre vines still produce fruit for Hewitson to make their ‘Old Garden’ varietal bottling. Those eight rows were planted by Friedrich Koch in Rowland Flat in 1853, and they’re thought to be the oldest productive vines of that variety in the world. The same is true for the 1848 grenache and semillon vines farmed by Marco Cirillo in Light Pass. The oldest cabernet sauvignon vines, again likely the world’s oldest productive vines, belong to Penfolds in their Kalimna Vineyard.

Arguably Barossa’s most famous name, Penfolds, was founded by Christopher and Mary Penfold in 1944, with Mary instrumental in setting it on the road – through her experimentation and advances in managing production and viticulture – to being the largest producer in the region by 1903, four years after her death. It would not be until the 1950s and the arrival of Max Schubert that a shift away from fortified wines would shape the business into what we recognise today.

Several of the Barossa names that persist to this day were essential pillars in the formative years, such as Samuel Smith who founded Yalumba in 1847. That’s still in family hands, while names such as Gramp have tentacles that run through the Barossa wine industry of today. Johann Gramp emigrated from Germany in 1837, and his plantings in 1847 near Jacob’s Creek would lay the foundation for the Orlando wine company, which remained in family hands until the 1970s.

Colin Gramp was Johann Gramp’s great-grandson, and he would revolutionise Barossa, and Australian, wine once he took the technical reins of Orlando in 1947 after a decorated career as an RAAF gunner in WW2. At the time, Australia was still enraptured with fortified wines, and the Barossa was prime territory for their production. While table wines were made, most wineries were geared to those styles, such as Seppeltsfield with their vast operation becoming the largest winery in the southern hemisphere in the latter half of the 19th century primarily on the strength of ‘port’ and ‘sherry’ production.

Gramp produced a red wine, from shiraz and cabernet sauvignon, from the 1947 vintage – Orlando ‘Special Reserve’ Claret – which represented a turning point in tastes shifting to table wines. That was reinforced by others, notably Cyril Henschke who began championing single vineyard wines in the ‘50s, and of course Max Schubert who was crafting the early vintages of Penfolds Grange. Gramp also introduced technology, chiefly temperature-controlled pressure thanks, which allowed him to introduce new styles.

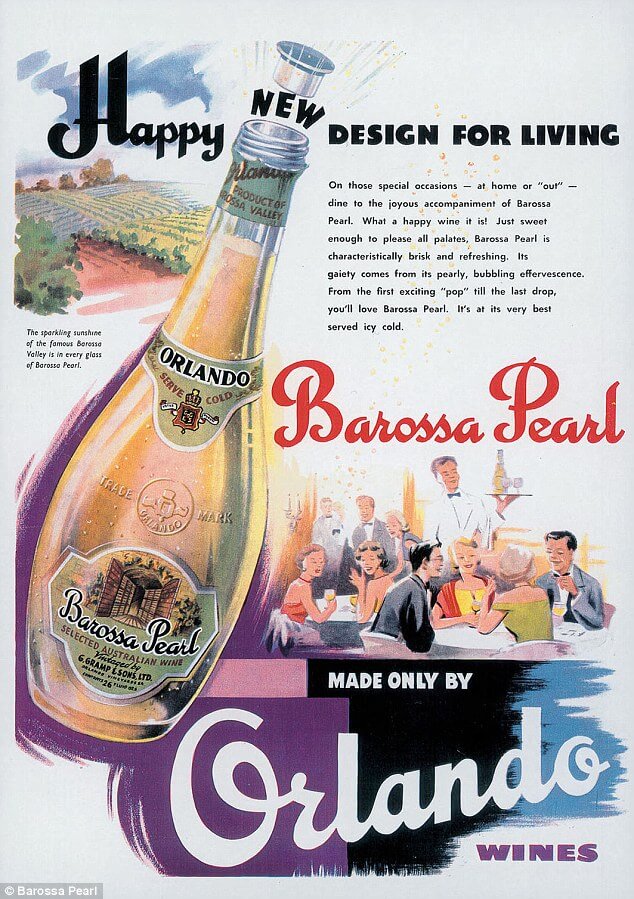

That equipment meant that making pristine white wines that retained bright primary flavours and stopped oxidation helped launch the riesling revolution that would persist until the 1980s when chardonnay forcefully grabbed the mic. It also meant that sparkling wine could be produced in bulk, and Barossa Pearl, a light, slightly sweet sparkling would come to dominate the market, selling in the tens of millions of bottles annually at its peak.

And while the seeds of a red table wine resurgence had been sown, the popularity of sparkling wine and riesling, and the dramatic decline in fortified wine consumption posed a problem for growers, and a threat to the Barossa’s most precious resource: old and ancient vines. Towards the late ‘70s, riesling was twice as valuable as shiraz, so much replanting was done, and with a general economic decline in the 1980s, many of those old vines were seen as a liability.

The infamous ‘vine pull’ scheme saw unprofitable vines removed or grafted through a government subsidy, and most of these were significantly old. That legacy of old vines is mostly absent around the country and indeed in Europe, where phylloxera wiped out so many vineyards. Nimble and effective government controls in the late 19th century saw the Barossa effectively quarantined, but about a 100 years later., the government of the day was undoing that work.

Thankfully, there was enough resistance from the likes of Peter Lehmann, Rocky O’Callaghan (Rockford), Neal and Lorraine Ashmead (Elderton), Grant Burge and Charles Melton, amongst others, who asserted themselves with table wines that supported their own vineyards as well as growers of old vine material with contracts that the big companies simply weren’t prepared to honour at a time of surplus. It was this foundation that would lead to a boom in Barossa red wine production through the 90s and shape the region of today.

The Barossa GI, which formalised the borders of the wine-growing zone, was declared in 1997, with the essential separation of the warmer valley floor and the cooler, elevated Eden Valley. The High Eden became a subregion in 2001. The Eden and Barossa Valleys are undoubtedly premium regions and represent a large zone, accounting for about 8 per cent of national vineyard land and 18 per cent of South Australian plantings.

Today, the Barossa is both a bastion of tradition and a fertile ground for forward thinking makers. Historic names like Yalumba, Henschke and Penfolds sit comfortably alongside newer but certainly established stars like Spinifex, Teusner, Tscharke and Torbreck, along with some of our most regarded avant-garde labels, like Sami-Odi and Ruggabellus. The excess of the late 1990s and early 2000s, where bigger was seen as better, has given way to a happily complex canvas where variety is key, with an increasing investment in climate-apt Mediterranean grapes jostling for attention with the old vine material and an evolving interest in old varieties that had fallen out of favour, such as cinsault and chenin blanc.