Tasmania has long been regarded as a place of great viticultural potential – the promised land for pinot noir, chardonnay and aromatic whites. But it is only in the last decade or so that the potential has been realised consistently and broadly across varieties and producers. Indeed, the fact that we still regard the state as one region – though it has seven established subregions – underlines that there is still much to do. The strength of Tasmanian wine today is underlined by this year’s Top 50, with six makers amongst the finalists, Mewstone, Quiet Mutiny, Sailor Seeks Horse, Small Island Wines, Two Tonne Tasmania and Wellington & Wolfe.

Tasmania is cold, but it’s also sunny, allowing for ripeness and freshness in grapes and wine. With that strong thread of natural acidity, it’s no wonder that it was pegged as ideal for sparkling wine production and an exciting prospect for aromatic whites, principally riesling. And though pinot noir and chardonnay are obvious candidates for sparkling, they were never going to be marginal prospects for still wines, like they are in the Champagne region. Though it did take some time for them to get their deserved foothold.

The youth of Tasmania as a wine growing region no doubt accounts for it being lumped in as one zone. When you consider that it takes three hours to drive from Devonport in the north to Hobart in the south, this seems somewhat too much of a generalisation.

Grape History

Tasmania had vines planted by William Bligh, along with some fruit trees, when the Bounty docked at Bruny Island in 1788. They were left to survive on their own, but only a lone apple tree did. There is documentation of wine being made by Bartholomew Broughton in 1826 from his Prospect Farm property, and there were vineyards both in the north and south by 1830. Vine cuttings from Tasmania are thought to have supplied some of Victoria and South Australia’s first vineyards. But Tasmania never developed a commercial industry of note, and though grown across the state, vines were more a hobby.

![]()

Meadowbank vineyard in Derwent Valley. Photo by Adam Gibson.

Tasmania was planted in earnest by Diego Bernacchi on Maria Island, off the south-east coast, in 1885. That Bernacchi’s name is only recognised by history buffs is testament to the fact that those vines did not succeed, and Tasmania was long seen as unsuitable for viticulture. It wasn’t until much later that the first tentative plantings took hold.

Jean Miguet planted grapes in 1956 for personal use, much as his family had done for generations in France. That vineyard, called La Provence, became the first successful commercial planting in Tasmania, and was initially made up of cuttings taken from backyard vines around Launceston, as well as vines bought from local nurseries. Down south, Claudio Alcorso began planting in 1958 for what would become Moorilla Estate, near Hobart.

Most early forays involved the planting of Bordeaux grapes, with pinot noir nothing more than an ornament.

Beyond Pinot Noir

There was a famous wine show result in Hobart in 1981 of a class consisting of cabernets from around the country, with the 1981 Heemskerk and 1981 Pipers Brook taking out two of the six gold medals awarded. We’ll let others judge the merits of tasting cabernet in the year of harvest, but that initial critical success, which was reinforced in the writings of the key wine scribe of the time (well, he still is), James Halliday, saw Bordeaux varieties flourish.

Today, while cabernet still has a meaningful presence, and can produce high-quality in the (few) appropriate sites, pinot noir is king. In fact, it has a dominance like no other grape in any other region. About 95 per cent of red plantings are pinot noir. Unsurprisingly, chardonnay is also heavily planted, but sauvignon blanc, riesling and pinot gris are major players, too, and in that order. Well, in terms of plantings at least, with riesling being arguably the key quality driver.

Wellington & Wolfe’s Hugh McCulloughs deep passion for riesling took him to the Apple Isle from the UK. After working around the world, Tasmania lodged in his psyche. “Tasmania is a place where the ancient land is abundant with life and the power to grow food and drinks that speak of place and are packed with flavour,” says McCullough. “I’d never seen the complexity and depth of flavour in any other region and so worked as hard as I could to move here to make something of my own from this land.”

Tasmania’s subregions

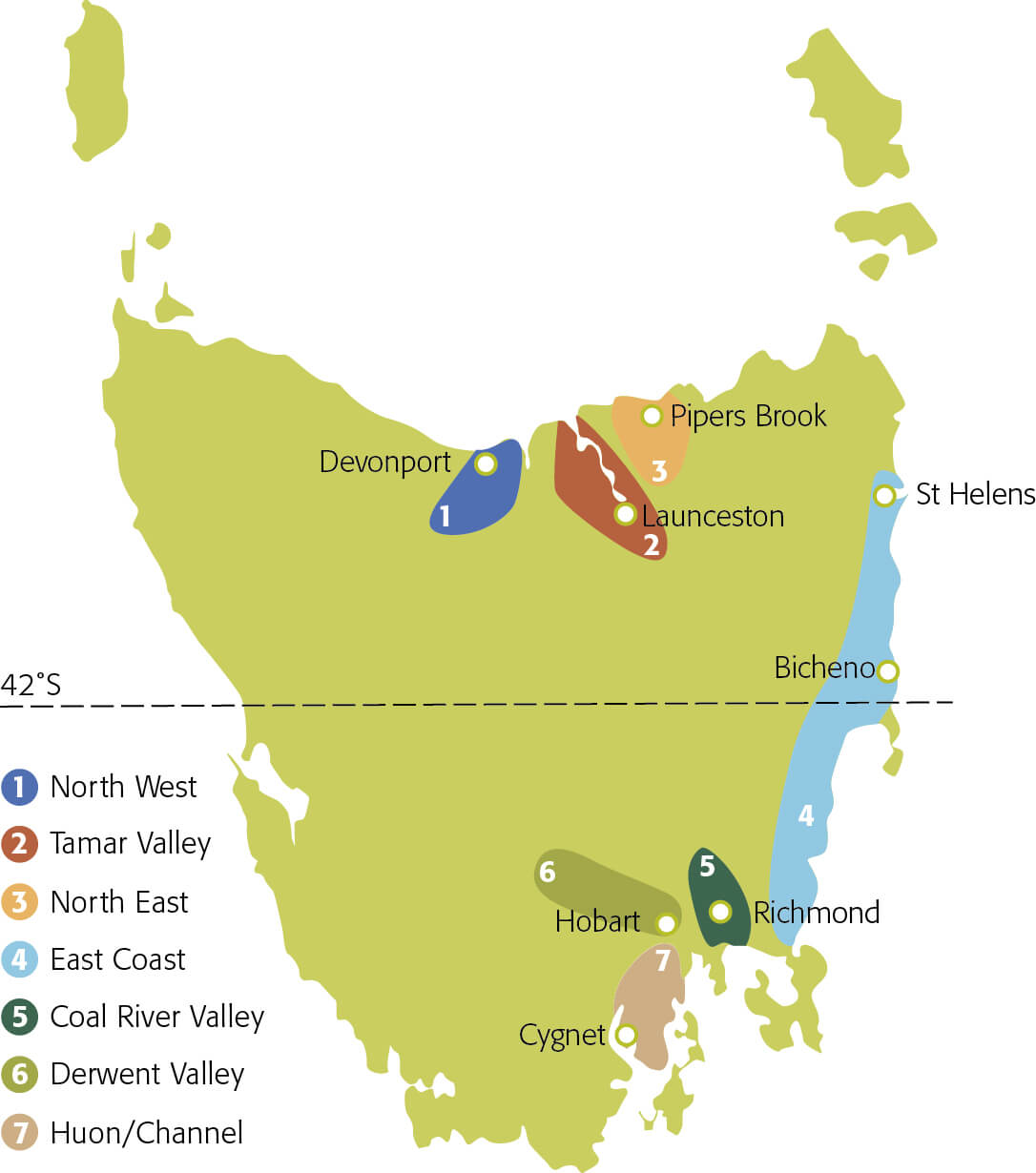

Tasmania is officially one GI, one region, but it has distinctly recognisable subregions that often have front-label prominence. The largest are the Tamar Valley in the north, which follows the Tamar River from the coast past Launceston, and the Coal River Valley in the south, which surrounds Richmond. The Derwent Valley is west of Coal River, with Hobart its anchor point, and to the south is the Huon Valley and d’Entrecasteaux Channel. Back up north, Pipers River is to the east of the Tamar, and to the west is the functionally titled North West wine region. The equally plainly named East Coast wine region extends from St Helens down to about Hobart’s latitude and is geographically the largest, producing about 20 per cent of the state’s wine.

![]()

Map of Tasmania’s wine sub-regions. Courtesy of Wine Tasmania.

The youth of Tasmania as a wine growing region no doubt accounts for it being lumped in as one zone. When you consider that it takes three hours to drive from Devonport in the north to Hobart in the south, this seems somewhat too much of a generalisation. But it’s not quite as ridiculous as catching all Victorian wines under a state banner. Victoria is bigger, sure, but it has regions that are starkly different, with the arid Murray Darling world’s away from the windswept cool of Henty. In Tasmania, from north to south, and east to west, there is more harmony.

![]()

Stoney Rise vineyard overlooking the Tamar River.

The subregional differences should be celebrated in Tasmania, but for most consumers they are details to be drilled down on, rather than ones of radical contrast. “I source fruit currently from the Tamar Valley and Pipers River in northern Tassie, but I think of myself as a Tasmanian winemaker,” says McCullough of his riesling-only project. “The whole state has such elegance and power, with many subtle differences in flavour and structure. It is significantly colder than any region on the mainland and that really does make a difference.”

From Mewstone (Jonathan Hughes, 2018 Best New Act) and Sailor Seeks Horse (Gilli and Paul Lipscombe, 2018 Winemaker’s Choice) in the extreme south, to the unique amphitheatre at Freycinet, in Bicheno, on the east coast, to Joe Holyman’s Stoney Rise vineyard up north on the Tamar River, a short drive from Launceston, Tasmanian vineyards may have many commonalities, but they are far from homogenous.

![]()

Jonathan Hughes preparing the ground for new riesling vines at Mewstone vineyard, overlooking the d’Entrecasteaux Channel – just south of Hobart.

Peter Dredge (2017 People’s Choice) sources fruit from across far flung corners to highlight this, with both pinot noir and chardonnay bottled as examples from east, south and north (Tasmania’s west is mostly national park), as well as a blend of the three, bottled under his Dr Edge label. Ricky Evans of Two Tonne Tasmania (2016 People’s Choice) has also added an east coast pinot noir to his Tamar Valley bottlings, again in the interests of shining a subregional spotlight.

Producer, producer, producer

Paul Lipscombe from Sailor Seeks Horse, in the cool of the Huon Valley, believes that this subregional definition will become very important over time, but, at present, the defining feature of Tasmanian wine is weighted towards nurture over nature.

“It’s a considerably more dynamic and exciting environment than 10 years ago.”

“One of the great things about Tasmania is the diversity of the state,” Lipscombe says. “From the north to the east to the south, the regions are massively different in terms of climate/soil and importantly, at the moment, people. The old saying of picking producer rather than region is a natural fit for Tasmania. We can, of course, see regional differences, but so often in a young area it is easier for the drinker to align with a producer who is doing something they find interesting and there is great diversity in producers now.”

That wasn’t always the case, with much of Tasmania’s wine historically being made by contract winemakers, and for a long time, the palates and methods of Andrew Hood and Julian Alcorso (Claudio Alcorso’s son) dominated Tasmanian wine. Whether fans or otherwise of their styles, it was more the variety of opinion and approach that was lacking, which was unlike any other premium wine region at the time.

![]()

Gilli and Paul Lipscombe at their Sailor Seeks Horse vineyard in the Huon Valley.

“We arrived in Tassie in 2010 and were pretty shocked at the general standard of wines here. The state was way behind on international trends towards sustainability in vineyards and freshness/complexity in wines,” says Lipscombe. “It felt nascent as an industry and subject to the palates of a very finite group of winemakers. That’s now changed, and an influx of people with a more global outlook and international experience with incredible producers are starting to explore the boundaries, whether that’s in terms of geography, picking dates, planting density, varieties, etc. It’s a considerably more dynamic and exciting environment than 10 years ago.”

That environment is certainly a vibrant one, with second-generation winemakers redefining already celebrated family estates, like Pooley’s Anna Pooley; Tasmanian makers who have garnered experience through travel, like Jonny Hughes, Greer Carland (Quiet Mutiny), Ricky Evans and James Broinowksi (Small Island Wines), with the latter first plying his trade as a sommelier; and those that have come to Tasmania for its incredible potential, like Gilli and Paul Lipscombe, Hugh McCullough and Peter Dredge.

Grape trials

And though it’s hard to imagine the spotlight shifting away from pinot noir anytime soon, with a premium associated with both fruit and wine, Lipscombe sees a more diverse varietal future as a preferred outcome. “There are actually spots here that probably don’t suit pinot that much, so seeing people start to explore other varieties is great,” he says. “There are so many cool climate varieties we can experiment with… We’ve planted some trousseau and hope to plant some ploussard soon, once we get some into the country. Aligoté and savagnin are also tempting.”

In addition to attempting to source vines common in Provence for his early plantings, Jean Miguet also assiduously pursued gamay, though none was available at the time. Interestingly, Gamay is now being championed by many growers and makers, with Small Island, Meadowbank (Peter Dredge, 2017 People’s Choice), Domaine Simha and Sinapius now making notable examples, though with many vine cuttings soon coming online, those ranks will swell considerably.

Today, Tasmania is widely and justifiably lauded, but the true excitement lays ahead. Fruit that was previously communicated in a narrow bandwidth is now finding new expression, but the delve into true subregional definition and varietal diversity has only just begun. The claims of Tasmania’s potential have long been vindicated, but the capacity for that reputation to be exponentially enhanced are immense.

The Wines

2018 Mewstone Riesling

This is ultra-zippy but not austere, instead it has layers of stone fruit, citrus, almost quince, but that hint at exoticism isn’t overplayed; spiced apple, dried pineapple, crystallised lemon peel, a touch of fresh mandarin peel, with a stony minerality and savoury complexity and just layers and layers of flavour. This has seen skins and oak, but it’s not what you think about. This is quite Germanic in feel, but on the trocken (dry) side, with plenty of density and matter, a slip of sugar, but with piles of acid and tension, too.

2018 Mewstone Pinot Noir

This is deeply flavoured and complex, with a wild brambly mesh of fruits, sour cherries and wild plums, with underbrush, bracken and a ferrous mineral note; a snaking trail of campfire smoke in the background. This needs time in glass or decanter to really express the fruit, with an array of red and black fruits emerging, fringed with spice and autumnal foresty notes. There’s a plump of poised richness here, sheathed in a web of fine tannin and driven by keen acid, with vivid flavours carrying long.

2018 Sailor Seeks Horse Chardonnay

Quite a fine and savoury nose with a lift of lemon peel, cool ripeness stone fruit, a saline/ozone character and a touch of oatcake. Oak sits in, and there’s no fat to flavour or mouth feel, just a cushion of leesy texture riding the acid. The impression here is one of minerality but not austerity, with a stone-fruit kernel burr of grip underlining the savoury finesse.

2018 Sailor Seeks Horse Pinot Noir

This is fragrant but with a dark-fruited brooding quality, with sour black berries, wild plum, red and black cherries, rhubarb and an autumnal feel, with undergrowth, a hint of freshly turned humus and a whisper of campfire. There’s intensity and concentration with a cool sourness of red berries and savoury tension accenting the riper notes. The palate is expressive, with a suppleness of tannin and bright acidity. This really builds with air, with the mineral/earthy side lending it real depth and complexity.

2019 Two Tonne Tasmania ‘TMV’ Pinot Noir

Spice dusted nose of wild red fruits, sour plum, morello and wild cherries, with a savoury herbal edge. The palate continues with wild red berries, savoury in their expression, with some assertive tannins and a spine of bright acidity.

2019 Two Tonne Tasmania ‘Dog and Wolf’ Pinot Noir

Lifted with wild cherry, sour raspberry, redcurrant and hints of darker fruits, with spice, white pepper and woodsmoke notes accenting. You can feel the impact of the whole bunch in the tussle between purely cast fruit and spice, between fleshiness and a clutch of tannin, which coupled with vibrant acidity gives this some serious structure.

2019 Quiet Mutiny ‘Charlotte’s Elusion’ Riesling

Fragrant nose bursting with floral/blossom and hints of stone fruit to match classic lemon and lime notes. There’s real depth of flavour and refinement, pure and vibrant in style, with a plump of texture, and a racy and persistent acid-driven palate and faint brush of grape tannin. This has lovely volume and fragrance, with it blossoming on the palate; it veers towards classic Australian riesling, but then veers away with more texture, nuanced structure and complex flavours.

2018 Quiet Mutiny ‘Venus Rising’ Pinot Noir

Full and expressive, this bursts from the glass with notes of ripe forest berries, ripe red and black cherries, spiced sour plum, a dusting of whole bunch spice and a gentle gloss of toasty oak. There’s a supple richness here, a pleasing generosity that never feels broad, which is pulled in with snappy tannins and bright acidity.

2019 Small Island Chardonnay

There’s a coolness to the nose, with white stone fruit, icy smashed green apple, a hint of brine, a subtle waxy fruit box character and orchard blossom notes. On the palate, there’s white nectarine, apple, dried peach and a savoury roughing up of stone fruit kernel notes. Oak is not a feature here, and the palate progresses with a lightly saline seasoning across the bright acid line that’s buffered with gently leesy texture and subtle tannic chew.

2019 Small Island ‘Black Label’ Pinot Noir

Finely ripe fruits, plenty of spice, some dark fruits, along with red berries, rhubarb, bay leaf and crushed autumn leaves. This is lifted and fresh, with real brightness, but not at the expense of complexity. In fact, it’s very layered, but it’s so poised it feels effortless, with minimal new oak and some whole bunch adding to the picture. There’s a supple, generally fleshy feel across the palate, with fine tannins and bright acidity.

2019 Wellington & Wolfe Tasmania Riesling

The nose is fine and delicately aromatic, with lifted notes of citrus flesh and peel, lime pith, lemon leaves, honey and floral/blossom notes. There’s a lacy fineness to this, with tension and drive accented with gentle texture and lemon barley water grip. This has seen some skin contact and oak maturation, but the impression is of purity and elegance, finishing dry, tight and racy.

2019 Wellington & Wolfe ‘Eylandt’ Riesling

There’s citrus and a little coolly ripe white stone fruit on the nose, with green apple, sweetgrass, lemongrass and stony minerals. Like the other W&W riesling, this has seen some skin contact and oak, but again the wine is all lithe poise and delicacy, with a linear and zippy feel across the palate. There’s texture and a chew to the structure, but it’s marked by tautness and clarity and delicacy of flavour.

See the full list of Top 50 winemakers in the 2020 Young Gun of Wine Awards here. Join in our virtual events here, and also vote on who wins the People’s Choice until June 1.