Geography, Soils & Climate

Tasmania is a region that is both easy and hard to generalise about. Legally, there it is one GI. Its border are the state borders, even though large portions of the island are allotted to national park and the like. It’s a blanket GI and one that desperately needs subregions. The Northern Territory and the ACT are the only other states/territories that are defined by their political borders. The former is more a formality (with no industry), while the latter is, well, essentially the same, with only one winery within the ACT boundary, and the Canberra District actually a wine region of New South Wales. Tasmania deserves better, subregions that have distinct general climatic and geological differences. Those zones are already established, with climatic and soil differences that demand individual classification, if not further division within those subregions.

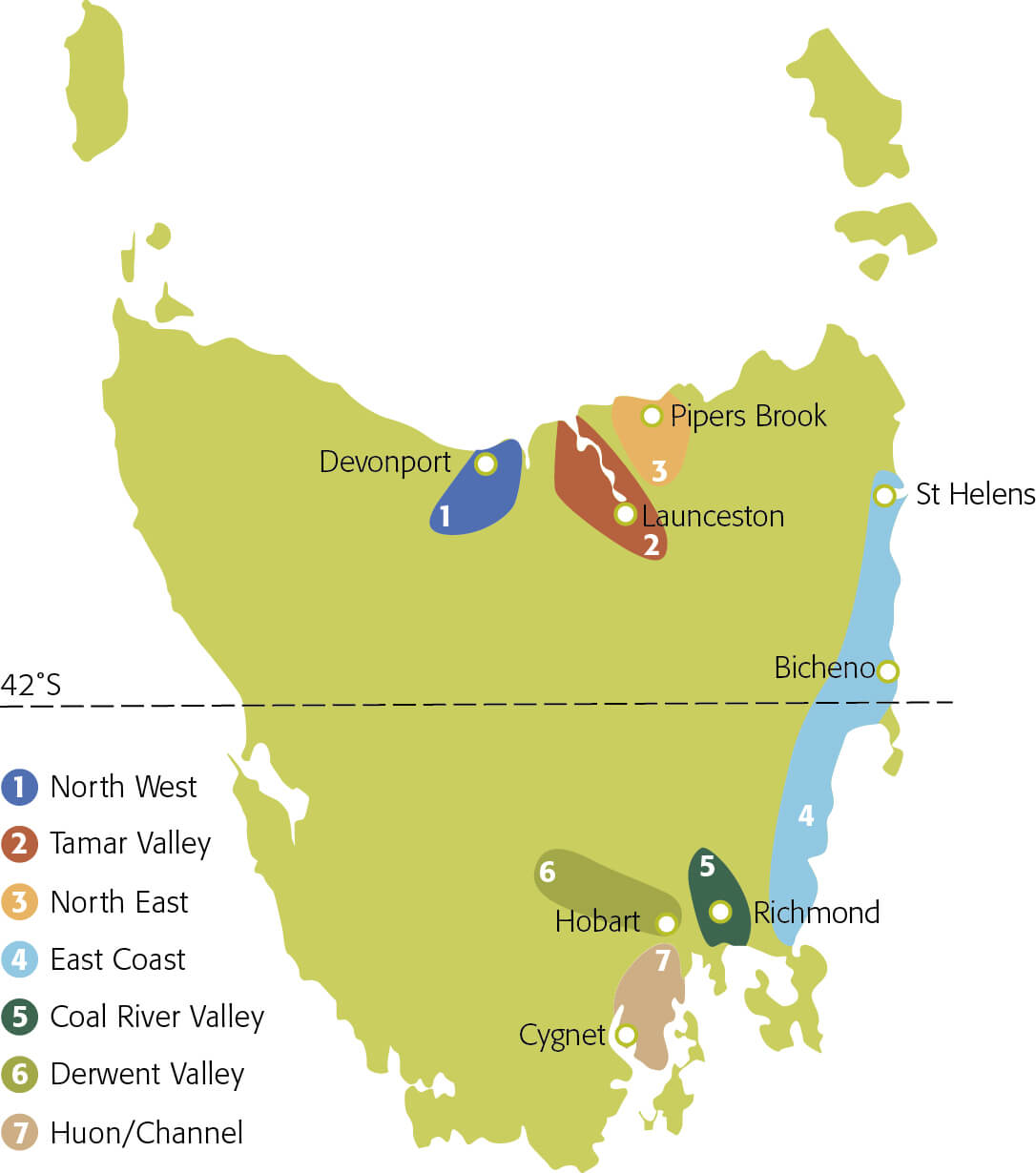

In the north-west, the aptly titled North West wine region is focused around Devonport, extending inland to around Sheffield. Heading east, the Tamar Valley wraps around Launceston and extends down the Tamar to Bass Straight. A little further west, Piper’s River is the other northern zone, while the rather long, if sparsely occupied, East Coast region extends from St Helens down the length of the coast, terminating a little further south than Hobart’s latitude. From the south, heading further west, the Coal River Valley has the town of Richmond at its approximate geographic centre, while the Derwent Valley extends to the northwest from Hobart. The Huon Valley and D’Entrecasteaux Channel make up the seventh region, and the most southerly, starting south of Hobart and extending past Cygnet.

The regions have a great deal of geological variation, with generalities about the subregions just that – soils can vary greatly over short distances. Pipers River, which is a sparkling wine centre, has friable, free-draining soils over sandstones and silt stones. Volcanic deposits of dolerite characterise the east of the state, with sandy loam, stony brown, and black, cracking topsoils all features. The Derwent Valley, Coal River Valley and Huon Valley contain sandstone and clay sediments under various duplex soils. The Tamar Valley features gravelly basalt over clay and limestone, along with sandy loam. Again, though, these are generalities, with a range of alluvial deposits also complexing the geology. Added to this is the potential for more subregions, with areas of great potential not yet planted.

Tasmania’s climate is essentially maritime, though some of the more inland sites lean towards continental conditions, with greater diurnal temperature shifts. Frost is a major limiting factor on viticulture, with significant wind also posing some challenges at budburst and flowering, but those same gusts help to moderate disease pressure. In general, the growing season is a long one with ample sunshine and relatively mild temperatures, set up by winter and spring rains, and supplemented by growing season falls. This well-timed rain, along with the attendant water resource for irrigation is a great advantage for much of Tasmania, though this benefit is not statewide. Hobart is the nation’s second driest capital, but the general availability of water means that irrigation can readily fill the gaps in the drier zones.