The Hunter Valley is a paradise for visitors. Pokolbin is a good two-hour drive from Sydney (and about an hour from Newcastle), making a day trip a fairly serious endeavour, but as a result, the Hunter is incredibly well serviced with accommodation, dining and all manner of other entertainment options, from premier golf courses to hot air ballooning. It is also in dynamic good health on the wine front, with veteran estates never stronger, and a new wave adding light and shade to one of Australia’s most unique and iconic regions. And it is also very well supplied with cellar doors, some 150 of them. The Hunter lays fair claim to be the pioneer of wine tourism, and it can also fairly claim to still be the leader. From major music events to intimate wine experiences, the Hunter has it all.

History

The Hunter Valley is Australia’s oldest wine region, shading Western Australia’s Swan Valley by a bit less than a decade. Those first plantings were somewhat furtive, with 8 hectares in the ground by 1823 on the banks of the Hunter River in what is now the Dalwood/Gresford area, between Maitland and Singleton.

When James Busby imported his collection of over 400 vine types in the 1830s, he planted cuttings in the Sydney Botanic Gardens as well as many of the same varieties, though perhaps not all, at his brother-in-law’s Hunter property, Kirkton. This was also around the time that plantings took off in earnest, with the land under vine rapidly swelling to over 200 hectares by 1840.

In the latter half of the 19th century, some the Hunter’s most famous names – Wilkinson, Lindeman, Tulloch, Tyrrell, Drayton – established their holdings, while a vineyard in Pokolbin planted by Charles King in 1880 would later form the core of the estate of one of this country’s greatest vignerons and visionaries. That site is the Old Hill Vineyard and it was bought in 1921 by Leontine O’Shea, along with an abutting parcel, at the urging of her 24-year-old son, Maurice.

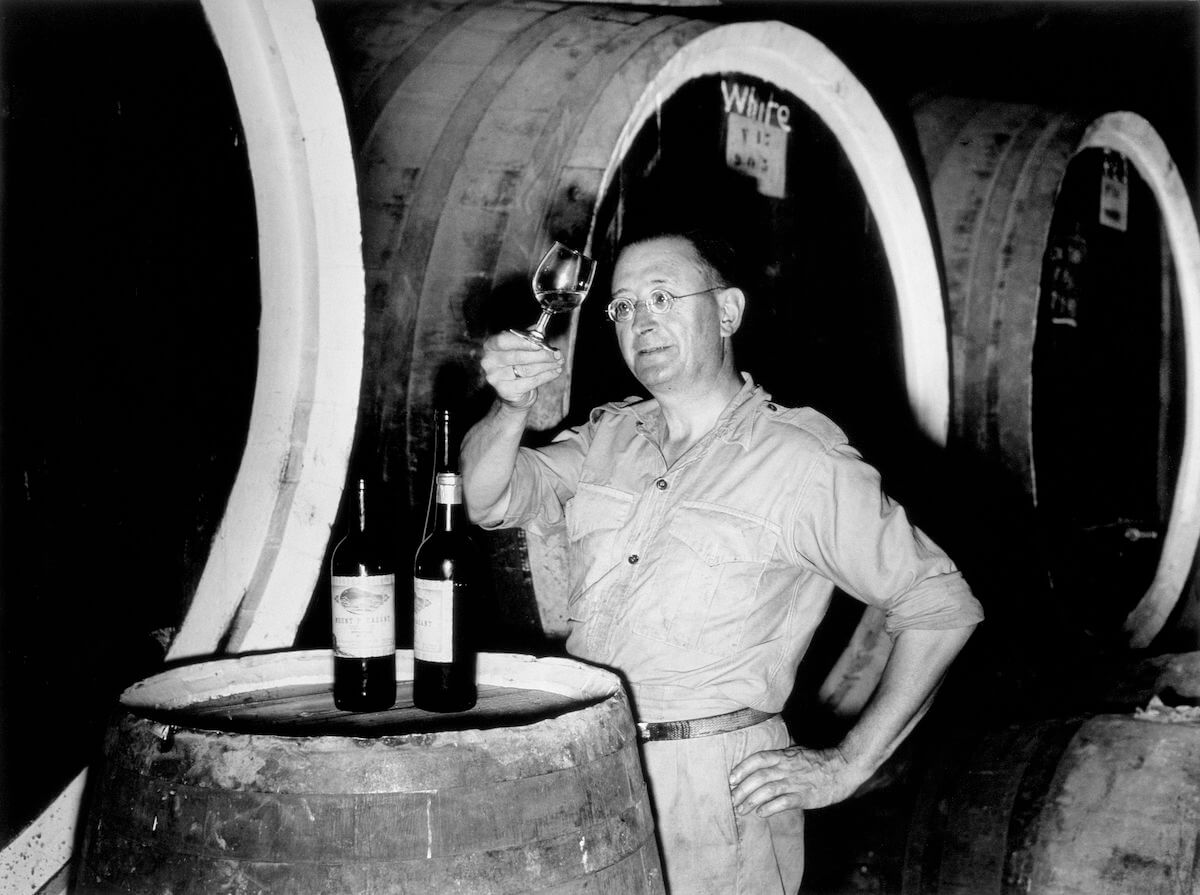

There is no doubt that Maurice O’Shea’s tenure at Mount Pleasant represents one of the most significant episodes in Australian wine, and the ripples are felt even now. O’Shea championed table wines when fortified wines were king. He carefully blended across varieties – including his iconic blending of pinot noir and shiraz – to make wines of a desired weight and aromatic detail, rather than lumping varieties in together indiscriminately. He even blended across white and red varieties, but never arbitrarily, and he focused on the differences that his sites afforded him. O’Shea also planted the Hunter’s most iconic semillon vineyard, Lovedale, in 1946.

Some of these ideas may seem commonplace now, but that’s how a legacy works. As said, the ripples are felt today. Although few examples exist today, the quality of O’Shea’s wines was borne out by their longevity, and not just as survivors, but wines that blossomed in the cellar, wines that were enhanced by time. And throughout his career – which was tragically cut short by his death at age 59 in 1958 – O’Shea never worked with modern equipment, and, in fact, never even had the luxury of electricity.

While many varieties were planted in the Hunter in the early days, the kingship of shiraz and semillon was soon established. Having said that, the varieties remained buried under confusing nomenclature for some time. Lindeman’s famously employed the term ‘Hunter River Burgundy’ for their shiraz, while they used ‘Hunter River White Burgundy’, ‘Hunter River Chablis’ and ‘Hunter River Riesling’ for their semillons. These were attempts at communicating style, with the semillon tags reflecting different levels of fruit weight in the bottled wines.

Although the Hunter never suffered the humiliations of the Yarra Valley and the like, whose vines were wiped out, it did suffer a decline in the early and mid-20th century – despite the best efforts of O’Shea – with a revival gaining pace in the 60s, coinciding with a slowly tightening embrace of table wines. Dr Max Lake, one of the Hunter’s great modern champions and characters (as well as being a prolific author), is thought to have planted the first vineyard in the Hunter since the 19th century, some 60-odd years after the turn of the century.

Lake was drawn to the area after being intrigued by an especially good bottle of Hunter Valley cabernet, hardly a regional strong suit, then or now. Lake was the leading hand surgeon at the time – another in the great tradition of medical professionals founding vineyards in the latter mid-20th century – and no doubt a very busy man, but the wine intrigued him enough to conduct soil tests to find a vineyard site to match and eventually exceed the wine that had so intrigued him.

Settling on a site on Broke Road in Pokolbin, opposite Mount Pleasant’s Rosehill Vineyard, Lake planted cabernet in 1963, then chardonnay in 1969, both of which were considered a ‘folly’ at the time. His wines were to become ground-breaking examples and were responsible for not just a boost to the Hunter, but also to the cause of Australian fine wine in general.

The epiphany that pushed Lake headlong into his ‘folly’ was a 1930 Dalwood cabernet blend, and he proclaimed it as the best wine he had ever tasted. It was made under the ownership of the then family-owned Penfolds, who had bought it from the pioneering Wyndham family.

The McGuigan family subsequently bought Dalwood in the 60s, renamed it Wyndham Estate and turned it into one of Australia’s biggest brands. They also equipped the headquarters to be the Hunter’s largest destination for dining, major events and the like, before being shuttered by Pernod Ricard many years later after their acquisition of the brand and its eventual decline. It has since been purchased and relaunched as Dalwood Estate once more – a little bit of history returning.

That association with big brands become a Hunter strength, and also its great burden. Scientific advancements in winemaking meant producing the “bottled sunshine” that Australia was to become famous for became a reliable proposition, and it was possible on a vast scale. Brands like Lindeman’s, Rosemount and Wyndham Estate become monolithic, but they were brands largely untethered from their regional origins, and eventually much of the excitement dissipated – well, from a quality perspective at least.

And while this corporatisation was diluting the real message, the Hunter was also rich with larger than life figures and regional champions, from Lake, to a young James Halliday co-founding Brokenwood, to the incomparable Len Evans. Helming the bullish growth of Rothbury Estate (which originally celebrated the Hunter in all its nuances), Evans exited after a hostile takeover and established Tower Estate, which became as famous for its wines as it did its five-star accommodation and restaurant.

Evans is one of the most celebrated advocates of Australian wine, and of Hunter Valley wine. Today, an invitation to the Len Evans Tutorial is one of the industry’s most prized tickets, with a wealth of extraordinary bottles opened and tasted under rigorous scrutiny from leading industry lights. It was founded by Evans as a means of training prospective wine show judges, and it has continued in this spirit after his death in 2006, slumped over the steering wheel of his car in the carpark of the Newcastle Hospital.

Today, the Hunter has fought to rebuild itself, and do so on largely classical lines. The great estates of Mount Pleasant and Tyrrell’s are making semillon, shiraz and chardonnay of supremely high quality, from everyday bottlings to refined classics, while there is a new guard both fine-tuning and innovating. Additionally, a history smudged somewhat by corporate winemaking and brand building is being restored. The old Ben Ean winery has been reinvigorated by the McGuigan and Peterson families, Tulloch Wines is back in family hands and the historic Dalwood has both had its name restored and is undergoing replanting to restore Spanish and Portuguese varieties that were part of the original estate. Indeed, the Hunter is as strong as ever, if not more so.